[This is the preface to The Book of Nocturnes: Philosophical Fragments by Matthew Nini (Spring Publications, forthcoming Fall 2025).]

Gott spricht zu jedem nur, eh er ihn macht,

dann geht er schweigend mit ihm aus der Nacht.

God speaks to each of us before he makes us, then goes silently with us out of the night. Because we have become artificers, masters of technique, we are under the impression that all things are crafted according to well-lit blueprints. The sleek edges and sharp corners that make up the geometry of the modern city are all drawn with care; the monuments of reason surround us. It is easy to forget that it has not always been this way. The meaning of the old adage, vita brevis, arslonga reveals as much: it is not, as one supposes, that art endures while life is fleeting; rather, that art, as what is artificial, the mastery of some technique, takes many lifetimes to master – long enough to forget not only the whole process of discovery, but who we were before we knew, when we stood in wonder before the uses of Reason. There is something in us that remains from these days of wonder and ignorance, a deep-seated nature underneath the technical dross. We are illuminated beings, but what is oldest in us is the kernel of darkness beneath the light of art, technique and reason. For reason does not come from reason; light does not beget light. Rather, dawn breaks from darkness; the night is what is older. We rational beings emerge from the night, the time of chaos and irrationality, and step into the dawn.

Works of philosophy are usually books that follow the logic of the day. It is from philosophy that all the modern sciences eventually emancipated themselves. In this way, it holds within itself the origins of the sciences, be they inductive or deductive, concerned with the natural and empirical or the human and subjective. The biologist, the physicist, the mathematician, the philologist, and social scientists of every stripe must proceed impartially and subject their findings to the most rigorous verifications. And to this we owe much. Yet this deployment of reason and its tools into the theatre of life also does it violence. The French term for a naval boarding is arraisonner. To reason, raisonner, is to forcefully take over, arraisonner.

Philosophy, however, is older than any of these particular fields. It contains the seeds of all these sciences within itself, and is exhausted neither by individual scientific disciplines, nor their sum. Part of it, therefore, remains within itself, an obscure part that cannot be subjugated by technique and artifice, because it is a life. This spark of life, which animates all the subsequent technical applications of philosophy, is what the Greeks called wonder. Life stands in wonder before itself, and this is the core of the philosophical, the beating heart that cannot be dissected without being stopped.

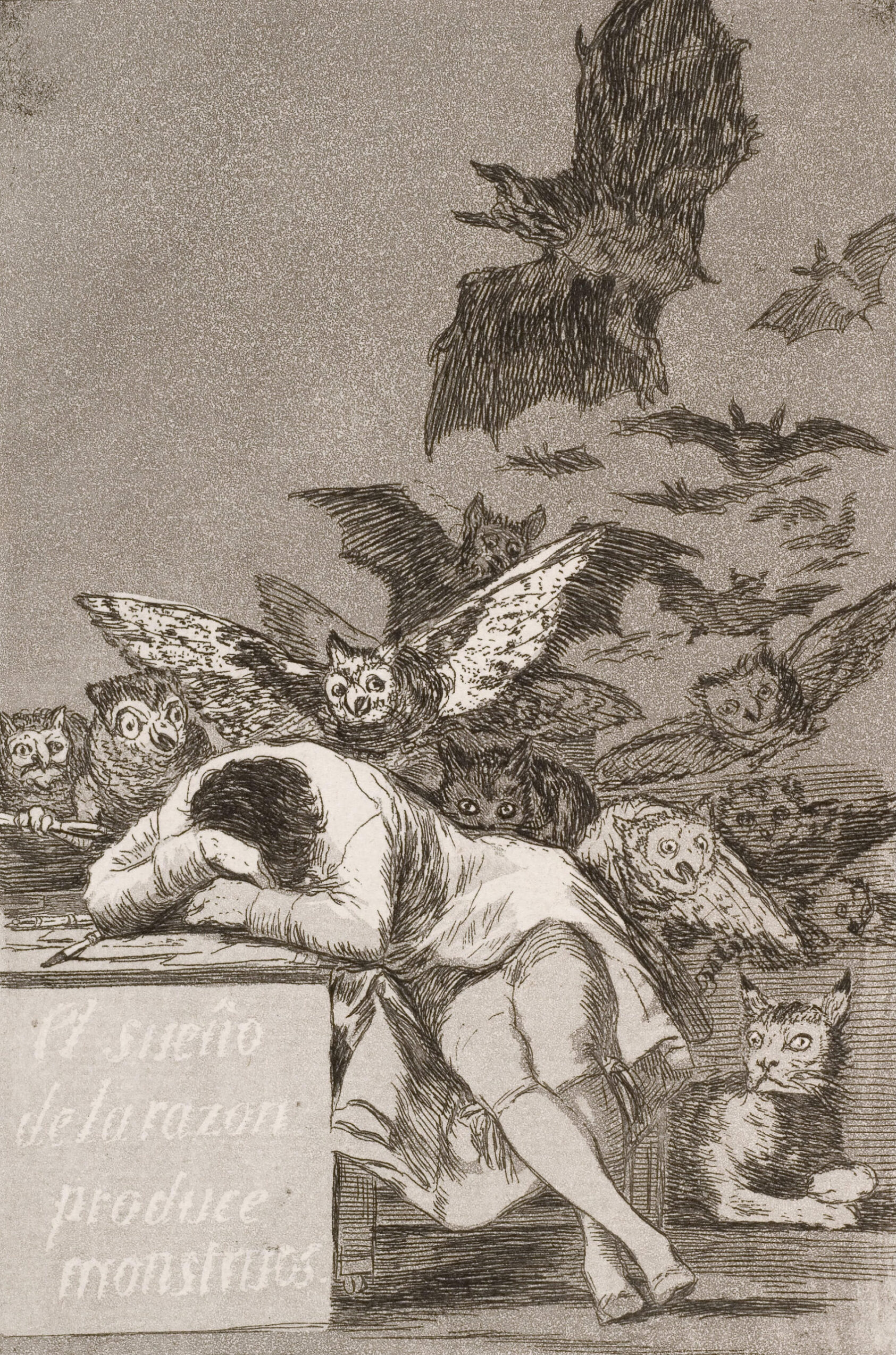

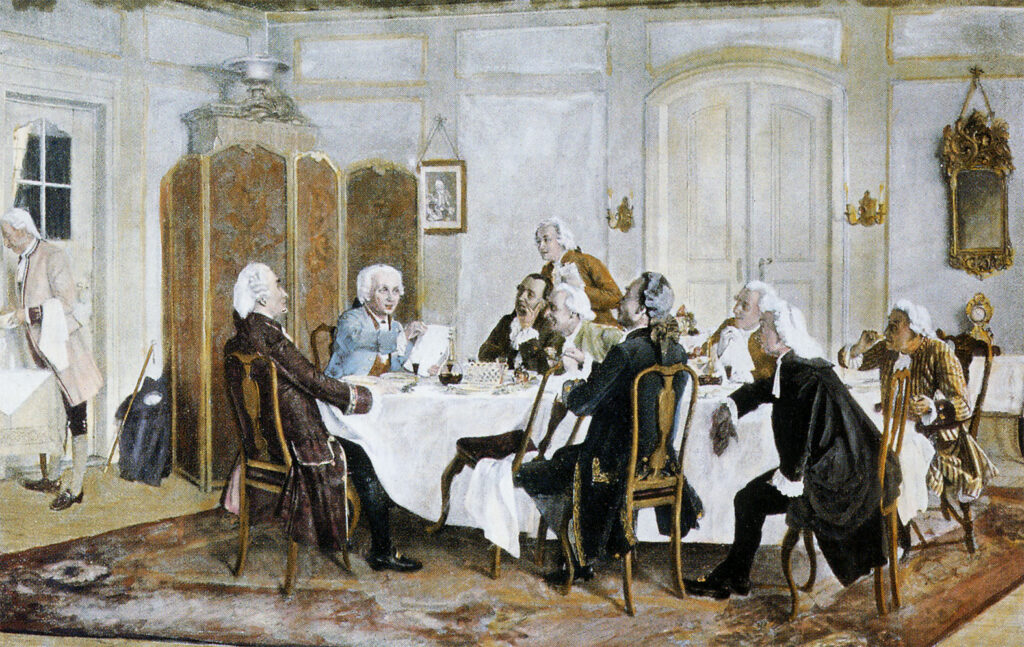

The place in which the inscrutable beating heart of wonder dwells is called the night. In the night, all the solid shapes of the day are still there, but they are obscured by darkness. The philosophy of night is therefore not opposed to the philosophy of day. It neither rearranges nor destroys. Instead, dim lights allow for new perspectives. Between the objects of reason, in the unfathomable interstices, fantasies, images, and impossible presences manifest themselves. The Apollonian rule of day – ordered, reasoned, oriented towards the good – is thereby suspended. But the night is not evil. It is merely what is before the reasoned journey towards the highest good has been knowingly begun. This, then, is thinking, but not yet reason. Yet because ours is inexorably the standpoint of reason, language, and logic, we can only see the night as reason’s precondition; not that which is prior to reason, since reason and the irrational, night and day, are two sides of the same, and come into being together, but that which is older than reason. As the philosopher Friedrich Schelling writes in his own book of the night, The Ages of the World, “Darkness and concealment are the character of the primordial age. All life first forms itself and comes into being in the night. It is for this reason that the ancients called Night the fertile mother of things. Together with Chaos, she is the oldest of all beings.”

What sort of book, then, is a philosophical investigation into the meaning of the night? It can only be a paradox, or better still, a riddle. While there are indeed night-books, the book itself is fundamentally a day object. Bound in language and constrained by concepts, books and their readers demand an intelligibility that can be subjected to the logic of artifice, the logic of day. If the night, and night-thinking, are to be grasped in language, it must be of a different kind, that of the mythical narrative, the εἰκὼς μῦθος. Art, religion, and imaginative story are the oblique paths that lead us into the night. A path is an established connection between one place and another. It always leads to a destination. But if we fix our eyes on the destination, we have abandoned the kind of thinking necessary for the night; to see that far, our eyes must be adjusted to day. As wanderers in the night, we might focus on the path itself, forgetting our point of origin and ignoring our destination. In order to be properly adjusted to our ambitions, writing, the use of language that is always subjected to reasons, must break off before a destination comes into view. Hence our mythical stories will have to be told as fragments.

Beyond the preface, this book is composed of fragments of various length. They are not aphorisms. This point cannot be stressed enough. The Greek ἀφορισμός refers to something that has been defined and set apart. It is meant to survive as a whole, the condensation of a principle into its most succinct form. What is enveloped in the aphorism invites being unfolded in commentary: wisdom literature, the domain of the aphorism, calls out for a midrash to apply it to daily life. Here, no midrash is possible because no commentary is necessary – the night is already life in its most intense form. At stake is being able to enter into this life with words without contaminating it with the principles that always stand hidden behind an aphorism. A fragment is merely a text that begins (or at least appears to begin) and does not resolve itself into a conclusion. By definition incomplete, the fragment always has unfinished business.

This book is therefore organized according to just such a fragmentary logic – that is, according to the demands of night-time thinking. The fragments herein are numbered, but their progression is not linear. If one chooses to read them in order, one will find a procession of ideas that moves as a spiral, beginning by articulating a theme, then developing groups of subordinate ideas, and finally linking them more closely, drawing them all in together at the end. It would be better to analyse the structure of the book using the methods of musicology rather than those of literature or philosophy: it is a philosophical sonata with an overture, several themes, their rearticulations in different keys, a coda. But the reader may choose to do otherwise. For while none of the fragments can be considered a completed whole, each stands alone; each is a nocturne in its own key. One can begin at any page, and read in any order. Many fragments do relate to the one that came before it or after it. Some also belong to a series. But these are not necessary relationships. Readers can jump around as they please. The way they connect the constellation of fragments is a kind composition in its own right; to really read a book is to be its co-author.

Given that books are daytime objects, a book of fragments such as this one is a kind of non-book, or anti-book. While it is primarily a philosophical work, it makes no arguments, and is therefore a non-treatise. It tells stories that go nowhere featuring characters that appear, disappear, and reappear, meaning it is a non-novel as well. It is also a non-history, a non-biography, a non-anthology, and non-poetry. The fragments are a mixture of the refined and unrefined, the integrated and appended. Some of them are merely summaries and interpretations of a single primary text, contributing to another “non-genre” of the book, the non-midrash. Once set in motion, the fragments take on a life of their own, defying both genre and author. And indeed, this non-book has a non-author; it is an unruly self-written book, a graphic causa sui into which author and reader are taken up.

Also taken up into the fragments is the book’s narrator (or perhaps more fittingly: non-narrator). N***, as we must call him, can only be a hypothesis of the reader. This scholar of night is not to be trusted. He exists only in the margins. Whether the cast of characters that N*** introduces are real, and whether the scholarship N*** presents is reliable, are for the reader to decide. I would advise treating him as you would the hypothetical author of some ancient text: he may or may not exist, and his opinions may or may not be borrowed, exaggerated, or corrupted. More pragmatically, you might think of him as a sort of spirit-guide, the Virgil who leads you along disjointed paths as you move through baroque cities, ancient ruins, vast libraries, insomniac nights and improbable encounters. He will help you make the night your own. If some corner of it enthuses you, know that you have likely discovered the mirror-image of the piece of night that is your own, the shadow of your daylight self. Be careful, lest it overwhelm you. Some things, dream-like, are best discarded at dawn.

Good night.