Should philosophers know business

and should businessmen know philosophy?

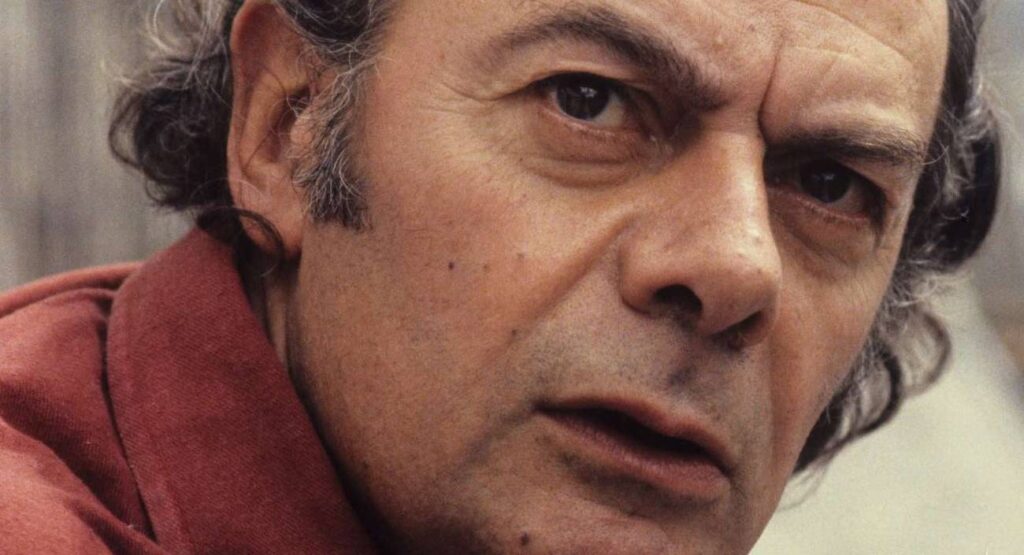

Some 2600 years ago, there was a guy who

“Fell into a well while doing astronomy, and looking up at the stars; they say a witty and charming Thracian slave girl joked that he was so eager to know about the things in the heavens that he omitted to notice what was in front of him, right by his feet.” (Plato, Theaetetus 174a, Rowe 2015: 45)

According to some, the lady was young and pretty; according to others, she was old and not so pretty (see Blumberg 2015). This detail may seem trivial, but it gains significance when we consider that she was not only a woman—young, beautiful, and enslaved—but also clearly intelligent and witty (this is especially notable given that this guy said that he is “blessed for being born as a man and not as a woman”, see Diels, Krantz 1952, Laertius 2013).

It is also said of the same man that:

“People were reproaching him for being poor, claiming that it showed his philosophy was useless. The story goes that he realized through his knowledge of the stars that a good olive harvest was coming. So, while it was still winter, he raised a little money and put a deposit on all the olive presses in Miletus and Chios for future lease. He hired them at a low rate, because no one was bidding against him. When the olive season came and many people suddenly sought olive presses at the same time, he hired them out at whatever rate he chose. He collected a lot of money, showing that philosophers could easily become wealthy if they wished, but that this is not their concern. Thales is said to have demonstrated his own wisdom in this way.” (Aristotle, Politics 1259a, C. D. C. Reeve 1998: 20; see Crawford and Sen 1998: 7 for the similar point that we are making here).

It appears probable that both events really occurred, with the same individual serving as the main character in each. However, it remains unclear whether they unfolded in the sequence initially stated. Even less certain is whether the second event was prompted by the first, specifically whether the establishment of the olive press business was motivated by the notion that this individual supposedly possessed no knowledge of ordinary earthly matters. Nevertheless, envisioning it as such does not significantly undermine the integrity of history.

Yet, the question remains: Who is the central figure in these two narratives? Some know him as the discoverer of the famous geometric theorem that states that

“If A, B, and C are distinct points on a circle where the line AC is a diameter, the angle ∠ ABC is a right angle.” (Heath 1021: 131)

Others know him as the greatest and first among the sages of Ancient Greece. He was an astronomer who described the position of Ursa Minor, and he thought the constellation might be useful as a guide for navigation at sea. He calculated the duration of the year and the timings of the equinoxes and solstices, he predicted the solar eclipse, and he is additionally attributed with calculating the position of the Pleiades. Last but not least, some know him as the first philosopher because he asked the question about the first principle (ἀρχή) of the world, concluding that it was water, and who first uttered the famous sentence: Know thyself (Γνῶθι σαυτόν) (see O’Grady 2002).

His name is Tales of Miletus.

Thales, therefore, stands as the pioneering philosopher who not only demonstrated the utility of his theoretical knowledge but also merged it with business acumen. He may well be regarded as the first entrepreneur who showcased the practical application of his scientific, theoretical, and philosophical ideas through a successful business venture.

Specifically, the first account pertains to his expertise in astronomy, which, apart from calculating the trajectory of a celestial body hurtling towards Earth, held limited practical implications (fortunately). The second account delves into his proficiency in business, which was intertwined with theoretical knowledge and found practical application through Thales’ role as a meteorologist. His ability to predict a bountiful olive harvest likely relied on his predictions of climatic conditions.

Symbolically speaking, we can perceive this entire narrative as a metaphor. While Thales might not have been the first philosopher, it is plausible that preceding philosophers may have engaged in business endeavors to validate the practicality of their scientific and philosophical theories. Nonetheless, the metaphor retains its strength and novelty: Philosophers can substantiate their philosophical prowess through practical knowledge, and perchance businessmen as well can demonstrate their business acumen through philosophical and scientific expertise.

Concerning Thales as the first philosopher, L. Cantor (2023) supplies solid arguments at least for doubt that Thales was the “first philosopher” and that philosophy has strictly “Greek origin”. She writes:

“It is widely believed that the ancient Greeks thought that Thales was the first philosopher, and that they therefore maintained that philosophy had a Greek origin. This paper challenges these assumptions, arguing that most ancient Greek thinkers who expressed views about the history and development of philosophy rejected both positions. I argue that not even Aristotle presented Thales as the first philosopher, and that doing so would have undermined his philosophical commitments and interests. Beyond Aristotle, the view that Thales was the first philosopher is attested almost nowhere in antiquity. In the classical, Hellenistic, and post-Hellenistic periods, we witness a marked tendency to locate the beginning of philosophy in a time going back further than Thales. Remarkably, ancient Greek thinkers most often traced the origins of philosophy to earlier non-Greek peoples. Contrary to the received view, then, I argue that (1) vanishingly few Greek writers pronounced Thales the first philosopher; and (2) most Greek thinkers did not even advocate a Greek origin of philosophy. Finally, I show that the view that philosophy originated with Thales (along with its misleading attribution to the Greeks in general) has roots in problematic, and in some cases manifestly racist, eighteenth-century historiography of philosophy.” (Cantor 2023: 727)

Let us return to the beginning of this narrative. What characterized the laughter of the Thracian woman? Was it a genuine expression of amusement, an act of mockery towards Thales, or a combination of both?

Regardless of the nature of her laughter, it is conceivable that it triggered a sense of indignation and motivation within the wisest of all Greeks, compelling him to demonstrate the practical applications of his theoretical scientific and philosophical knowledge.

By analogy, we can envision a highly accomplished entrepreneur who, while conducting business, commits a major blunder in fundamental areas such as economics, business administration, and other related fields including social psychology, ethics, law, and politics (as evidenced by numerous historical and contemporary examples).

Imagine a scenario where a young employee ridicules this businessperson on a social platform. Irrespective of the nature of the mockery, we can visualize how this entrepreneur might, through the study of economic, legal, social, political, psychological, ethical, and philosophical theories, prove his success by applying them.

Consequently, a legitimate question arises: What are the philosophical and ethical theories, if any, that a businessman should be familiar with in order to achieve greater success in business?

The obvious and existing candidates include ethics in business ethics, social philosophy in corporate social responsibility, bioethics in sustainability, psychology and social psychology in human resource management, management and leadership. However, epistemology, philosophy of technology, philosophy of culture, philosophy of communication, and even ontology may also be among the candidates.

References

Aristotle (1998) Politics, C. D. C. Reeve (ed.), Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Company.

Blumenberg, H. (2015) The Laughter of the Thracian Woman: A Protohistory of Theory, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Diels, H., Krantz, W. (1952) Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Berlin: Weidmann.

Cantor, L. (2023) “Thales – the ‘first philosopher’? A troubled chapter in the historiography of philosophy”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 30:5, 727-750.

Crawford, G. and Sen, R. (1996) Derivatives for Decision Makers: Strategic Management Issues, New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Heath, T. L. (1921) A History of Greek Mathematics: From Thales to Euclid, Vol. I. Oxford.

Laertius, D. (2013) Lives of Eminent Philosophers, T. Dorandi (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Grady, P. F. (2002) Thales of Miletus: The Beginnings of Western Science and Philosophy, London and New York: Routledge.

Plato (2015) Theaetetus and Sophist, C. Rowe (ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.